Abstract

The viability of the news industry has been in rapid decline since the mid-2000s. Many studies have documented how search and social media platforms have disrupted news publishers’ relationships with audiences and advertisers by appropriating control over news distribution and revenue. Ethnographic research in newsrooms over the past 15 years shows how the power of the platforms have reshaped the practices of journalism. But little attention has been paid to the exercise of agency within news organizations that shifted power to the logics and logistics of Big Tech. I present here a critical analysis of how news publishers themselves helped precipitate the crisis in news by enthusiastically adopting Big Tech platform technologies and audience-building strategies. I use Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory and Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory to explore the restructuring of the news industry by the sociotechnical practices and surveillance economics of today’s dominating platforms. Leveraging Michel Serres’ discourse on social and informational parasitism, I present a research framework for assessing symbiotic and parasitic relationships between journalism and Big Tech using historical, quantitative, and qualitative methods, and to identify where news publishers may still have agency to begin resolving the crisis. And I suggest the urgency of this research framework as publishers rapidly adopt generative AI technologies.

Note: While this analysis is focused on the news industry in the U.S. and local news in particular, a review of literature on the state of news around the world indicates that the crisis is international in scope.

INTRODUCTION

Journalism has reached a point of crisis, as proprietary platforms have enclosed much of the space where media is increasingly published, distributed, and consumed, that is, the Internet and social media. What once seemed like an opportunity for greater public access to news and promotion of informed democracy is increasingly controlled by the platforms, and “any remaining allure of the Web 2.0 model has been overshadowed by the near-global dominance of a small number of proprietary digital platforms” (Burgess & Hurcombe, 2019, p.361).

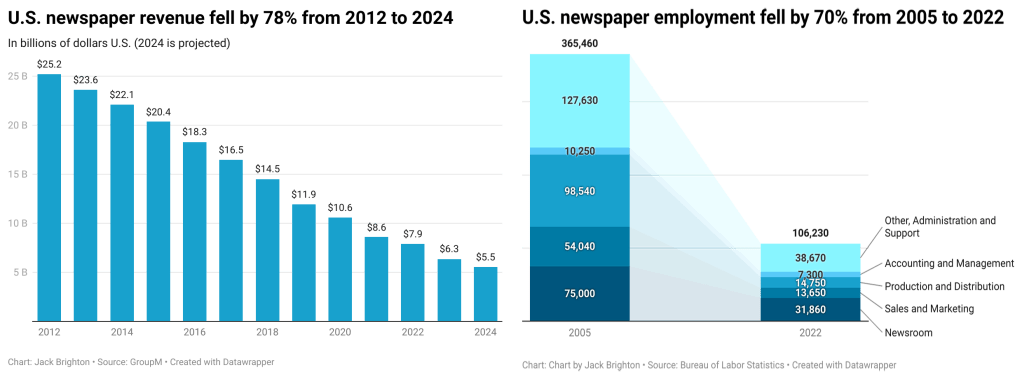

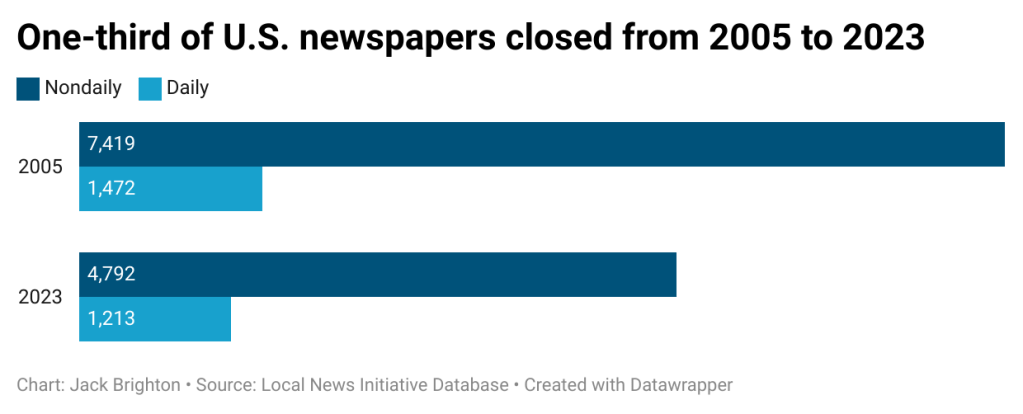

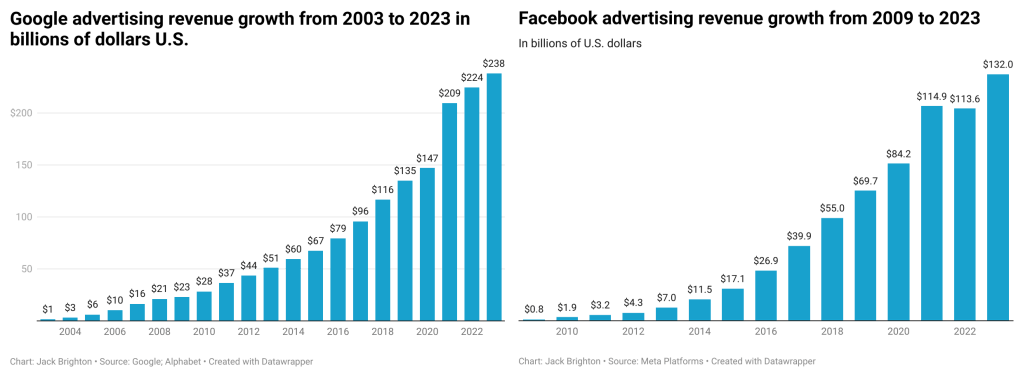

During the 2000s, in hopes of reaching larger audiences, news organizations began posting their stories on social media and gave the platforms nearly continuous free promotion. As social media became an intermediary between publishers and their audience, publishers lost control over distribution, branding, and advertising revenue, and the platforms themselves became de facto publishers of news produced by professional journalists. By 2016 Google and Facebook came to dominate digital advertising (Bell & Owen, 2017), while ad revenue for U.S. newspapers collapsed from $50 billion U.S. in 2005 to less than $6 billion in 2023 (Abernathy 2020, 2023). During this period almost two-thirds of U.S. newspaper journalists lost their jobs, and some 2,900 newspapers closed, with an average of more than two additional newspapers closing each week, and some 1,800 communities became part of the U.S.’s expanding news deserts. In more than half of U.S. counties, residents now have no or very limited access to local news, whether print, broadcast, or digital (Abernathy, 2020, 2023). News conglomerates and hedge funds have sought to profit from the crisis by consolidating local newspapers into chains while cutting local journalists, office staff, and facilities, resulting in a significant shift away from local and state news reporting (Abernathy 2020, 2023; Ewens, Gupta & Howell 2023; Peterson & Dunaway 2023; Susca 2024). Jeffrey Goldberg, Editor-in-Chief of The Atlantic, put the consequences in stark terms: “To look at cities that used to be served by newsrooms of 300, or 500 journalists, now reduced to virtually nothing, is terrible. This is the way democracy decomposes. We’re sleepwalking into an absolute disaster” (Darcy 2024).

This matters because:

- Effective local journalism connects people to the civic life of their community. I understand this from my own professional experience as a local journalist.

- Research shows that without access to local news reporting, citizens are less engaged in community affairs and governance, and less likely to vote (Rubado & Jennings 2020).

- Loss of local newspapers has been shown to increase political polarization, as people rely more on partisan news sources (Darr & Hitt et al., 2018).

- Communities without a credible local news outlet are more likely to be affected by misinformation and propaganda on social media platforms (Pickard, 2020).

For more than a century, U.S. newspapers have relied on advertising for about 80 percent of their revenue. As Victor Picard (2020) notes, “this structural vulnerability helps explain why the US newspaper industry is suffering more than many of its international counterparts” (p.75). As newspaper advertising revenues rapidly collapsed after 2010, Google’s advertising revenue grew from less the $1 billion U.S. in 2001 to more than $238 in 2023, and Facebook’s ad revenue increased from less than $1 billion U.S. in 2009 to $132 billion in 2023.

As news organizations attempted to adapt to the dominance of search and social media companies they became dependent on their administrative functions, allowing the platforms to write the rules (and code) that determines success in the news industry. Stories must now conform to demands of the social media ecosystem, and publishers are at the mercy of opaque feed algorithms. News organizations are now dependent on a digital content distribution system they do not control. In short, Big Tech has fundamentally restructured the business of news and the work practices of journalism (Bell & Owen, 2017; Caplan & boyd, 2018).

While many scholars have addressed the dominance of Big Tech platforms over the news industry, there remains a theory gap in the literature concerning the agency of specific platform technologies adopted by news organizations and their role in shifting news publishing and revenue to the platforms. My research framework addresses this gap by incorporating a hybrid mix of critical theories including structuration theory (Giddens 1984), actor-network theory (Latour 2005), and parasite theory (Serres 1982). Together they provide a multiplex lens for analysis of empirical data gathered through historical research on news and technology, and quantitative and qualitative data from sources and field work in today’s news industry.

In addition, it is vital to understand the functions of specific technologies used in the relationship between news and Big Tech platforms as interconnected sociotechnical systems, the workflows in which they operate, and the understandings and motivations of the people who implement them. The technical and the human details both matter.

Sources used in this analysis

My research is informed by a broad review of existing literature on the history of journalism, the relationships between journalism and technology, and a deep exploration of theoretical lenses used by scholars who produced that work. Quantitative and historical data on the news crisis comes from scholarly publications, news industry sources, and analytical reports provided by nonpartisan research centers such as the Pew Research Center, the Nieman Journalism Lab, the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, the Northwestern University Local News Initiative, and the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at UNC. These primary sources provide important historical and industry data along with many insightful analyses. A broad review of academic research on digital journalism and the crisis in news in the age of Big Tech revealed gaps in existing theoretical approaches, which I address here. As further context for my work, over the past 30 years I experienced the development of the news crisis as a multimedia producer and reporter at Illinois Public Media at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I became deeply interested in using technology to extend the positive social impact of journalism, and became a web developer for nonprofit news organizations during the rise of today’s dominant search and social media platforms. It would be fair to say that I participated in that rise, which I only understood in retrospect as the news crisis unfolded. My research is a product of my professional experience in news and Internet technology, and my later turn to scholarship grounded in critical theory.

A Critical Research Framework

I present here a brief summary of my research framework along with examples of its application.

Structuration Theory

Structuration theory holds that social structures and human agency are mutually constructed over space and time. As Anthony Giddens (1984), the originator of the theory puts it, “structuration theory is based on the proposition that structure is always both enabling and constraining, in view of the inherent relation between structure and agency (and agency and power)” (p.168). For Giddens, only humans have a role as actors, and social structure is continuously recreated or modified by their actions. Use of structuration in research is about identifying structures, rules and resources within social systems, which can lead to an analysis of where power resides and where agency can make a difference that makes a difference.

Structuration theory has been used by many scholars to analyze change in social structures, agency, and power in newswork (Usher 2103; Webster 2011). News organizations are now dependent on social media platforms for distribution. Demands to publish and continuously update news stories on multiple platforms have greatly accelerated the pace for news workers (Usher 2012, 2013; Siapera 2015). Digital disruption has reshaped labor relationships between management and news workers, with more precarious employment, part time work, and freelance labor (Siapera 2015). Production of multimedia for news websites and a plethora of social media platforms has required adaptations in roles and skills in the newsroom, and new relationships with complex technologies and platforms controlled by third parties. Digital news must conform to ever-changing social media algorithms, formats, and standards. There are increased demands to “engage” with members of the audience on multiple social media platforms. The chase for likes, shares, and clicks has become normalized in the editorial workflow. In large news organizations there are front- and back-end web developers and digital “product owners,” and IT staff supporting everyone in the organization. There are often multiple dependencies on Amazon Web Services and other cloud providers. There are large budgets for digital hardware and software, and licenses for Microsoft Office and Adobe Creative Suite. As most local news organizations can’t afford most of these things, they outsource critical functions or make do with what they’ve got.

Meanwhile, platforms appropriate newsroom labor and audience data for their profit-making activities such as targeted advertising and trade on data markets, leading to direct integration of news work with the infrastructures of surveillance capitalism.

Actor-network Theory

Actor-network theory (ANT) holds that society is the outcome of interactions within connected systems of people, technologies, and even ideas, called actor-networks. Each entity in the actor-network is considered an actant. ANTs “infra-language” is very distinct from structuration theory, but there is growing interest in using a hybrid of both theories among journalism and information systems researchers (Lewis & Westlund 2014, Wiard 2019). Actor-networks are typically in a state of continuous change, but can reach a state of stability. In ANT terms, this stable state becomes a “black box” which appears to be fixed and no longer changeable. This is important for recognizing when change appears cemented in a given sociotechnical system, like a technical standard, a programming language, or practices with technologies that appear mature or strongly deterministic.

Latour explains ANT as a method to identify nodes of agency in networks of humans, machines, ideas, and even words, as potentially powerful entities. ANT research requires careful examination of relations between all elements of a given network. Latour explains that “with Actor-Network you may describe something that doesn’t look at all like a network…it all depends on the sort of action that is flowing” from one actor to another. “It’s the work, the movement, and the flow, and the changes that should be stressed” (Latour 2007, pp.142-143). Like structuration theory, ANT is concerned with where power resides. Unlike structuration theory, an actor-network includes non-human agents. ANT traces “translations,” meaning actions that create change in a network at any given moment, while structuration theory identifies the recursive reshaping of social structures over space and time. The two theories can be complementary in information systems research, a framework Brooks and Atkinson (2004) call “StructurANTion.” This framework is extended here for theory-informed empirical research using quantitative and qualitative methods to collect data on the extent of changes in agency, power, and structuration in sociotechnical systems. For that we turn to social theorist and philosopher Michel Serres’ parasite theory for assessing asymmetrical power relations and resource flows as new technologies are introduced into organizational structures and practices.

Parasite Theory

Although commonly used as a term describing a biological organism that preys upon a host, the root of the the word parasite, originating from Latin and Greek, refers to a person eating at another’s table. Or as Serres puts it in his inimitable poetic style, “the one eating next to, soon eating at the expense of, always eats the same thing, the host, and this eternal host gives over and over, constantly, till he breaks, even until death” (Serres 1982, p.7).

Serres’ book The Parasite presents a series of parables that have served scholars in many different fields as descriptive of asymmetrical relations of power and exploitation. “Unlike predators, who consume their prey whole, the parasite does not exhaust production,” writes social psychologist Steven D. Brown (2013). “It would be better to say that the parasite parasitizes reproduction, the propagation of production, rather than production per se. The parasite redirects reproduction, it steers it in a new direction favourable to it” (p.89). M.G.E Kelly (2010) argues that “our world system is marked by a parasitic imperialism of rich sovereign states over poor ones, carried on at the level of populations” (p.1). Jeff Robbins’ (2019) poses the question “If technology is a parasite masquerading as a symbiont – are we the host?” (p.1). The question could apply to our personal relationships with search engines, social media, mobile devices, generative AI systems and more. Many scholars are addressing the social harms of these technologies, such as addiction, radicalization, and cognitive atrophy from offloading intellectual tasks to machines. Parasitic systems “nudge” us to make choices that benefit the system (Gandy, 1993). Frischmann & Selinger (2018) refer to this as techno-social engineering, whereby “we are being conditioned to obey. More precisely, we’re being conditioned to want to obey” (p.6). The tools don’t just do our bidding; they’re smart enough to get us to do theirs.

I don’t mean to suggest that all human relationships with technology, as a general category, are parasitic. The word symbiosis may be a better term for relationships where exchange of energy, information, and resources is a net positive for both parasite and host. Technology as an agent (“actant” in Latour’s terms) may benefit an organization and benefit from it, in which case the relationship can be symbiotic. Alternatively, technology may reshape and consume an organization’s energy and resources and gain power and order at the organization’s expense, in which case the relationship becomes parasitic (Brown 2013; Burgess & Hurcombe 2019; Pasquinelli 2009; Serres 1982). Serres refers to this as the abuse value, “a one way relation of taking without giving” (Brown 2002, p.17). The suggestion here is that this abuse value can be empirically measured.

The implementation of parasitic technologies can be understood as generating entropy, “a movement from order to disorder, where energy is consumed and inevitably lost in the process” (Bradley 2022, p.459). Bradley (like Robbins) invokes the second law of thermodynamics in the context of social life. The parasite gains the energy and order it consumes from the host. Carr-Chellman, Kitchell & Freeman (2020) discuss this unequal exchange between parasite and host as negentropy, where negentropy “is the reversal of entropy within the organization” (p.275). Lilian Kroth (2024) refers to an imbalance of energy between related systems as an “entropic difference” wherein chaos and order are not separate entities, but codependent principles that “form part of the same difference” (p.22). In parasitic relationships, then, the parasite gains order (negentropy) while host reaps chaos (entropy).

While my framework offers a conceptual device grounded in critical theory, it requires empirical research to acquire data for analysis. Both quantitative and qualitative methods are used to identify shifts of power, energy, and order, so as to provide a measure of entropic difference (or abuse value) between journalism and the platforms. For example, data on the news industry’s sharp decline in advertising revenue shows an increase in industry-wide entropy, while data on the rapid increase in advertising revenue for Google and Facebook shows an increase in negentropy. Critical analysis of information flows and power relations between news organizations and Big Tech strongly suggests this is more than a simple correlation.

Examples of analysis using the framework

For example, Facebook’s News Feed fundamentally restructured work practices and resource allocation throughout the news industry while consuming its primary source of revenue. In an atmosphere of “move fast and break things” and a fear of missing out, publishers conformed to the requirements of Facebook’s feed algorithm and content standards, and were (initially) rewarded with growth in their Facebook audience (Caplan & boyd, 2018). This provided incentive to publish and actively (and continuously) promote their organizational pages on Facebook, and importantly Facebook itself. In consequence, Facebook quickly grew its user base, including a significant share of news audiences, while also diverting advertising revenues from news publishers and extracting and monetizing the personal data of Facebook users (Nielsen & Ganter, 2017; Whittaker, 2019). A preponderance of ethnographic research in newsrooms has shown that this relationship consumed a significant measure of newsroom resources and energy while attempting to comply with the rules of the feed algorithm (Nielsen & Ganter 2017; Poell, Neiborg & van Dijck 2019), which has often changed without warning (Poell & van Dijck 2014).

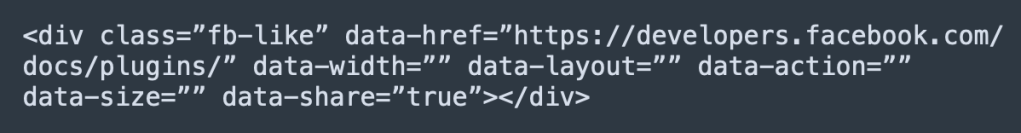

Another example: Facebook’s Like button plugin allows visitors to “like” a story on a news publishers’ website, just as they might “like” it on Facebook. Code to embed the Like button on a web page also allows Facebook to use tracking technologies (e.g. the Facebook tracking pixel) on the publisher’s site to capture personal data from the publishers’ audience. Facebook provides publishers with many other “social plugins,” all of which extract and monetize the personal data of visitors to publishers’ sites (Bell & Owen, 2017).

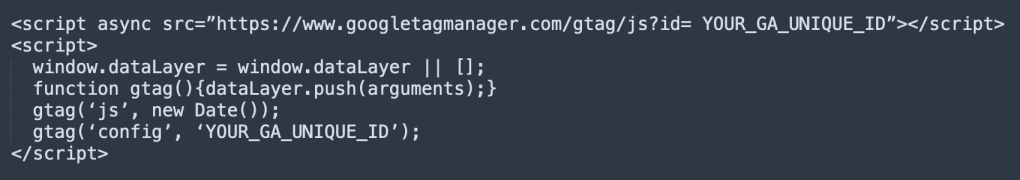

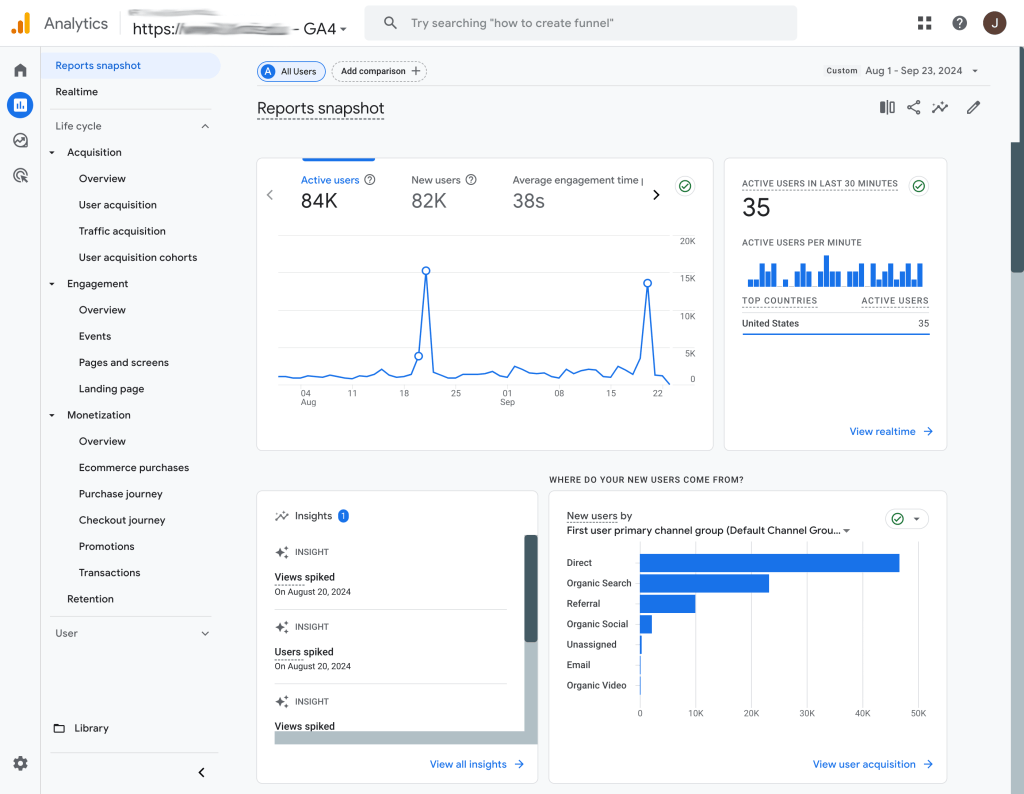

Google provides publishers with a suite of tools for analyzing their website traffic, which have been shown to restructure editorial practices in favor of click-bait headlines and a focus on “going viral” (Bell & Owen, 2017). In many newsrooms, story choices and evaluation of journalistic work are shaped by website and social media metrics. Large news organizations have teams focused solely on audience analytics, search engine optimization, and A/B headline testing using platforms like Google Analytics (GA) and Chartbeat (Lamot, Kenza & Paulssen, 2019), while small news publishers serving local, minority, and disadvantaged communities can’t afford to compete. As with Facebook, Google’s suite of tools for publishers collects personal data for Google to use in behavioral advertising and other forms of monetization.

I have documented elsewhere how Google Analytics was instrumental in the ascension of Google as the largest advertising company worldwide, and the key role it played in the rapid growth of AdTech and surveillance capitalism since 2005 (Zuboff 2019). Google’s analytics and advertising platforms have reshaped entire industries, and training people how to implement and use them has become an industry itself. The code that enables GA to harvest website traffic data is now embedded in 49.6 percent of all websites (Web Technology Surveys, 2024).

The Facebook news feed and “like” button and Google Analytics are examples of specific technologies with agency in the relationship between news and Big Tech, but they are far from the only agents. Humans also exercise agency, including people in the news industry who made choices to engage in a power relationship that has become parasitic. I suggest that identifying how and where they surrendered agency in that relationship is a necessary step to reclaiming it.

The critical research methodology outlined here would also be useful for analyzing parasitic relationships in many other contexts, and where agency still exists to restore a balance of power.

Conclusion

Since the mid-2000s search and social media platforms have profoundly reshaped news production and distribution and undermined the viability of news publishers. As a corollary the media ecosystem has become saturated with misinformation and partisan bias, contributing to a “dramatic loss of confidence in mainstream media” (Whittaker, 2019, p.5) and an unstable public sphere. Consequences of this disruption arguably include an increase in social polarization, disruption of democratic processes and institutions, and dramatic political upsets like the passage of Brexit in the UK and a global upsurge in support for authoritarian and xenophobic leaders. The ubiquity of disinformation and social and political discord surrounding the 2024 U.S. presidential election are stark reminders of a news system in crisis.

Social and political impacts from the decline of news are an increasingly vital area of research, but the questions I pose here are much more modest: To what degree is the relationship between Big Tech and news publishers symbiotic or parasitic? How can this best be measured? And how can this analysis inform better choices for societal welfare and equity in times of sociotechnical innovation? The research framework outlined here is based on a critical theory-focused analysis of existing scholarship on Big Tech and the decline of news, and a mix of qualitative and quantitative data gathered through industry and field research. Qualitative methods include ethnographies and interviews of participants in news and technology actor-networks, e.g. journalists, managers, and technology developers. Quantitative research includes data on growth or decline in the affected industries, e.g. the number of operating newsrooms and news deserts, jobs lost, gained, or restructured, transformations in the flow of revenue and capital, and other metrics relevant to the viability of news publishers. This empirical research can be extended further, for example with data on the number of original local stories produced and the page count of news publications, and the extent to which online and nonprofit news organizations are “filling the news hole” left by failed newspapers. It should also be extended to research on the status of news industry in other nations, as other scholars are addressing.

The value of theory in this work is not simply to understand the structures, but to provide a cognitive device to assist the work in reshaping them. The sociotechnical systems under study are comprised of humans, technologies, power, and agency. In ANT terms we are seeking to analyze and describe ongoing transformations in these systems. In structuration theory terms, we are studying key events where the actors exercised agency on the basis of unfounded assumptions and unacknowledged conditions, resulting in the unintended consequences the news industry is experiencing today. As structuration is a recursive process, deeper insight on the conditions and consequences of prior action could provide new opportunities to restore agency, resources, and order within the news industry and a better future for journalism. The importance of this work is especially urgent for local news organizations and those serving historically and economically disadvantaged populations and communities.

Coda

Research incorporating critical theory is inescapably a value-laden proposition, as “critical theory questions all thought and practices that justify or uphold domination and exploitation (Fuchs, 2016, p.9). Critical theory is rooted in values of liberation and social equity, and critical theory scholars make judgments about structures of oppression which privilege some classes to the disadvantage of others (Leckie et al., 2010). The domination of news distribution by a small number of technology corporations has implications for how society produces, stores, and accesses information, since information processes and information itself are part of the “given” aspects of social structures. Thus, the importance of a news ecosystem that is not dominated by actors who seek to change things for their own private benefit at the expense of others, and the value of information systems that prioritize social equity and common good. That is the stance of this research framework.

In this context it is important to note that many of the same dominant technology companies which have undermined the news industry over the past two decades are now promoting AI as a way to “save” journalism, while further consolidating their control over information and its infrastructures. The stakes for the future of news could hardly be higher.

REFERENCES

Abernathy, Penelope Muse. (2020). News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive? The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, Hussman School of Journalism and Media, Hussman School of Journalism and Media. https://www.usnewsdeserts.com/reports/news-deserts-and-ghost-newspapers-will-local-news-survive/

Abernathy, Penelope Muse. 2023. “The State of Local News – 2023.” Evanston, Illinois: Local News Initiative, Northwestern University. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/projects/state-of-local-news/2023/report/.

Bell, E., & Owen, T. (2017). The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley reengineered journalism. Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Colombia University. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/platform-press-how-silicon-valley-reengineered-journalism.php/

Bradley, Joff P. N. 2022. “Experiments in Negentropic Knowledge: Bernard Stiegler and the Philosophy of Education II.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 54 (5): 459–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.1999228.

Brooks, Laurence, and Chris Atkinson. 2004. “Structurantion in Research and Practice: Representing Actor Networks Their Structurated Orders and Translations.” In Information Systems Research: Relevant Theory and Informed Practice, 389–409. IFIP International Federation for Information Processing. Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-8095-6_22.

Brown, S. D. (2013). In Praise of the Parasite: The Dark Organizational Theory of Michel Serres. Informática na educação: teoria & prática, 16(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-1654.36928.

Burgess, J., & Hurcombe, E. (2019). Digital Journalism as Symptom, Response, and Agent of Change in the Platformed Media Environment. Digital Journalism, 7(3), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1556313.

Caplan, R., & boyd, danah. (2018). Isomorphism Through Algorithms: Institutional Dependencies in the Case of Facebook. Big Data & Society, 5(1), 2053951718757253. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718757253.

Carr-Chellman, Ali, Allen Kitchel, and Sydney Freeman. 2020. “Negentropy: Energy Creating Tools for Organizational Development.” TechTrends 64 (2): 275–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00448-5.

Darcy, Oliver. 2024. “Jeffrey Goldberg: Newsroom Decay Is How ‘Democracy Decomposes.’” Status. October 13, 2024. https://www.status.news/p/atlantic-jeffrey-goldberg-2024-interview.

Darr, Joshua P, Matthew P Hitt, and Johanna L Dunaway. 2018. “Newspaper Closures Polarize Voting Behavior.” Journal of Communication 68 (6): 1007–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy051.

Ewens, Michael, Arpit Gupta, and Sabrina T. Howell. 2023. “Local Journalism under Private Equity Ownership.” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3939405.

Frischmann, Brett, and Evan Selinger. 2018. Re-Engineering Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316544846.

Fuchs, C. (2003). Structuration Theory and Self-Organization. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 16(2), 133–167. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022889627100.

Fuchs, C. (2016). Critical Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy (pp. 1–20). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118766804.wbiect002.

Gandy, Oscar H. 1993. The Panoptic Sort: A Political Economy of Personal Information. Critical Studies in Communication and in the Cultural Industries. Boulder: Westview Press, Inc.

Giddens, A. (1981). A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism. Vol. 1: Power, Propert and the State, Macmillan, London/Basingstoke.

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Kelly, M. G. E. 2010. “International Biopolitics: Foucault, Globalisation and Imperialism.” Theoria 57 (123): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3167/th.2010.5712301.

Kroth, Lilian. 2024. “Entropy and Entropic Differences in the Work of Michel Serres.” Theory, Culture & Society 41 (2): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764231187593.

Lamot, K., & Paulussen, S. (2020). Six Uses of Analytics: Digital Editors’ Perceptions of Audience Analytics in the Newsroom. Journalism Practice, 14(3), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1617043.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press.

Leckie, G. J., Given, L. M., & Buschman, J. (Eds.). (2010). Critical Theory for Library and Information Science: Exploring the Social from Across the Disciplines. Libraries Unlimited.

Lewis, S. C., & Westlund, O. (2015). Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities in Cross-Media News Work. Digital Journalism, 3(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927986.

Myllylahti, M. “We need to talk about metrics.” Themes and critical debates in contemporary journalism (2017): 87-94.

Nielsen, R. K., & Ganter, S. A. (2017). Dealing with digital intermediaries: A case study of the relations between publishers and platforms. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817701318.

Pasquinelli, M. (2009). Google’s PageRank Algorithm: A Diagram of the Cognitive Capitalism and the Rentier of the Common Intellect. In Deep Search: The Politics of Search Beyond Google. Studienverlag & Transaction Publishers.

Peterson, Erik, and Johanna Dunaway. 2023. “The New News Barons: Investment Ownership Reduces Newspaper Reporting Capacity.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 707 (1): 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162231211426.

Pickard, Victor. 2020. “How Commercialism Degrades Journalism.” In Democracy without Journalism?: Confronting the Misinformation Society, 0. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190946753.003.0004.

Pickard, Victor. 2020. “Journalism’s Market Failure Is a Crisis for Democracy.” Harvard Business Review, March 12, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/03/journalisms-market-failure-is-a-crisis-for-democracy.

Plesner, U. (2009). An actor-network perspective on changing work practices: Communication technologies as actants in newswork. Journalism, 10(5), 604–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884909106535.

Poell, Thomas, and José van Dijck. 2014. “Social Media and Journalistic Independence.” In Media Independence: Working with Freedom or Working for Free?, 182–201. London: Routledge.

Poell, Thomas, David Nieborg, and José van Dijck. 2019. “Platformisation.” Internet Policy Review 8 (4). https://policyreview.info/concepts/platformisation.

Robbins, Jeff. 2019. “If Technology Is a Parasite Masquerading as a Symbiont—Are We the Host?” IEEE Technology and Society Magazine 38 (3): 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/MTS.2019.2930267.

Rubado, Meghan E., and Jay T. Jennings. 2020. “Political Consequences of the Endangered Local Watchdog: Newspaper Decline and Mayoral Elections in the United States.” Urban Affairs Review 56 (5): 1327–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419838058.

Serres, M. (2007). The Parasite. University of Minnesota Press. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/the-parasite.

Siapera, E. (2015). Journalism’s Dilemmas: Internet Challenges for Professional Journalism and Media Sustainability. In Journalism at risk—Threats, challenges and perspectives. Council of Europe Publishing. https://book.coe.int/en/human-rights-and-democracy/6675-journalism-at-risk.html

Susca, Margot. 2024. Hedged: How Private Investment Funds Helped Destroy American Newspapers and Undermine Democracy. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/jj.9474322.

Turner, Fred. 2005. “Actor‐Networking the News.” Social Epistemology 19 (4): 321–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691720500145407.

Usher, Nikki. 2012. “Reshaping the Public Radio Newsroom for the Digital Future.” Radio Journal 10 (January): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1386/rjao.10.1.65-1.

Usher, Nikki. (2013). Marketplace public radio and news routines reconsidered: Between structures and agents. Journalism, 14(6), 807–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884912455903.

Web Technology Surveys. n.d. “W3Techs – Extensive and Reliable Web Technology Surveys.” Accessed September 30, 2024. https://w3techs.com/.

Webster, James G. 2011. “The Duality of Media: A Structurational Theory of Public Attention.” Communication Theory 21 (1): 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01375.x.

Whittaker, J. P. (2019). Tech Giants, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of Journalism. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351013758.

Wiard, Victor. 2019. “Actor-Network Theory and Journalism.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.774.

Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. First edition. New York: PublicAffairs.