I wrote this paper while researching specific aspects of online privacy as a PhD student at the University of Illinois School of Information Sciences. It has not been peer-reviewed or published elsewhere, and I’m posting it here to invite comments, criticism, and suggestions. Please feel free to send me email at jackb at illinois dot edu, or twitter message me @ jackbrighton.

Abstract

The term “AdTech” has become shorthand for the technologies, platforms, and practices of online advertising. The term is often used by advocates of privacy protection in the current period where advertising is based on increasingly pervasive surveillance of online interactions, and commodification of personal data. Most criticism of AdTech has focused on online tracking which captures user data, and digital advertising which exploits it for commercial purposes. Almost entirely lost in the discussion is the role of analytics platforms, which process personal data and make it actionable for targeted advertising. I argue that the role of analytics is key to the rise of AdTech, and has not been given the critical attention it deserves. This article presents a general history of online analytics technology and methods over the past 25 years, and a specific history of the Google Analytics platform as it became an essential piece of Google’s dominance in digital advertising worldwide. I show that Google rose to dominance through strategic acquisitions of the technologies of online tracking, analytics, and advertising. Through the lens of information history research, I examine the influence of Google Analytics in the commodification of personal data and the emergence of the commercial Internet. I propose a three-part conceptual model of AdTech, comprised of online tracking, analytics, and advertising. And I suggest this model may be useful in future research on the technologies, practices, and consequences of the commercial Internet for personal privacy and security, and as a framework for improvements in privacy policies and regulations.

Introduction

Technologies of online surveillance are increasingly pervasive, resulting in massive data sets about users of the World Wide Web and mobile devices. The scope of this data includes users’ browsing history, demographics, interests, behavioral patterns, and detailed information about their interactions with websites and apps across the Internet. In the aggregate, this data has become highly valuable as a commodity, resulting in new enterprises that collect, trade, monetize, and exploit personal data for commercial purposes such as targeted advertising. Often referred to as “AdTech,” these practices are of growing concern to privacy scholars and advocates for consumer protection. Consumers are also becoming more concerned about online privacy intrusions, and pressure is growing toward new regulatory protections.

Much has been written about online tracking, the nature and extent of the tracked data, and the current deficit in regulation of associated privacy intrusions. But a key piece of the AdTech infrastructure has been almost entirely overlooked: the use of analytical platforms to make sense of online personal data, and to deliver it as an input to a global network of advertising.

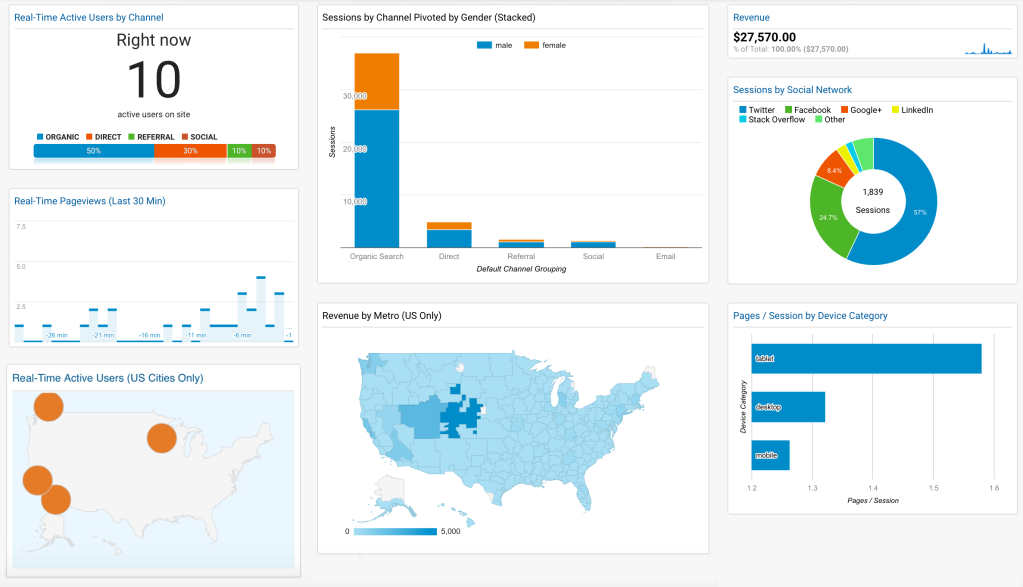

By far the most important of these analytical tools is Google Analytics (GA). Google offers the GA platform for free to websites and app developers, in exchange for access to the user data captured by its tracking technologies. The GA dashboard, accessible via web browser, provides website operators a wide range of anonymized data on their audience and their use of their site, including real-time site traffic; numbers of visitors and visits; visitor demographics, geolocation, interests, technology, and level of engagement; sources and referral path of site traffic; search terms used to find the site; metrics on page views; site speed performance; custom “events” definable by the website operator such as clicks on specific links; and user “conversions” to goals like subscribing to a newsletter or completing a purchase. GA is integrated with Google’s advertising platforms, AdSense and AdExchange, allowing advertisers (and Google) to measure their ad impressions, clicks, and revenue.

Additionally, the Google Tag Manager enables site operators to add trackers from third parties including social media platforms, other advertising networks, and other Google products such as YouTube. The operator need only add a single first-party Google Analytics tracker to their site, enabling third-party trackers to come along for the ride. This can result in a single web page loading hundreds of trackers and ad server requests (Fou 2020).

GA is now used by 54.6 percent of websites worldwide, and dominates the market of online traffic analysis tools with a share of 83.9 percent (W3Techs, 2020). It has become the largest entry point for the collection, aggregation, and analysis of online user personal data for commercial purposes in the world. And it has helped Google become the largest advertising company worldwide.

In this paper I present a brief history of online analytics technologies and their role in the infrastructure of AdTech. I find that analytics play a central role in the story as an essential component residing between online tracking and advertising. Since any true story about online analytics becomes a story about Google, I focus here on Google Analytics. The question I want to answer is “What is the role of Google Analytics in the global collection and aggregation of online personal data?” Many related research questions may flow from this.

I begin by summarizing a history of online user tracking, and some key events and actors that influenced the emergence of the commercial web and Google as the digital advertising market leader. Next I introduce the Google Analytics platform and discuss its importance in enabling online tracking and user data aggregation. I’ll discuss the extent of personal data that can be captured via GA’s tracking methods and tools, and how GA is used to enable user tracking by hundreds of third-parties. Finally, I present a three-part model of AdTech, consisting of tracking, analytics, and advertising. I propose this model as a lens for further research on commodification of personal data, and as a framework for policy-making to improve the protection of online privacy.

Sources

This study draws from a wide variety of resources including academic research, news reports, industry sources, and online privacy advocates. To understand the functionality of the Google Analytics platform in more depth I reviewed documentation provided by Google, which is written and bifurcated for two distinct audiences: web developers and marketing professionals.

GA documentation presents several research challenges. Its volume is vast, and covers different versions of GA as the platform has been further developed over the past 15 years. Documentation pages for the most recent previous version, which cover key concepts and implementation methods, often link to non-existent documentation pages for the current version for “updates.” I found it possible to assemble a reasonably detailed understanding of past and current versions by following the documentation trail from past to present versions.

Industry sources proved to be a different kind of challenge, as their motivations often seem to be promotional or self-serving and their claims dubious. Authors of corporate promotional and marketing materials are of course less inclined to be critical of their own companies, technologies, and practices, and I found that some of these sources contradict others on important facts. I was very cautious about taking this material at face value, and made every effort to verify claims by interrogating multiple sources. When in doubt, I rejected the claims.

While reviewing academic research on the methods and impact of AdTech, I was surprised to find only rare mentions of analytics. I found that GA makes only a brief appearance in scholarly literature, and its functionality and role is almost entirely unexamined. This gap suggests an opportunity for further research, and I hope to provide a useful entry point here.

Research Methods

I used methods of history research to explore the story of AdTech as entrepreneurs and investors sought an Internet business model based on advertising. I examined the evolution of online analytics through the lens of information history, a field of information science research focusing on the role of information systems and practices in a given society, and how “information affected, and is affected by, the social, political, economic and cultural climates of the time” (Weller, 2007).

More specifically, the information history lens of “theme” suggested by Alistair Black and Bonnie Mak framed my review of the sources used in this study, and provided context for my analysis of Google Analytics’ role in online surveillance and advertising (Black & Mak 2020). The theme chosen here is online analytics, and I explored the history of advertising on the web using this theme as a focal point.

I also conducted empirical assessments of various websites by using several tools, including FouAnalytics’ tracking detector, The Markup’s Blacklight privacy inspector, and the DevTools applications inspector in Google Chrome. Additional live data was drawn from the WhoTracksMe tracking analysis tool, which aggregates anonymous tracking data from some 800 million webpage loads monthly via Cliqz and Ghostery browser extensions, with the consent of users. This data provides convincing evidence of Google Analytics’ pervasiveness on websites worldwide, and its relevance to many privacy challenges we are experiencing today.

Findings

Much of the research and critical discussion of online user privacy focuses on tracking. In this study I define tracking as the collection of data from a single user as they interact with different websites and mobile apps. An important privacy liability of tracking is that this data can be associated with users by assigning each individual a unique identifier. This allows the individual to be tracked at sites they visit across the web and mobile devices, adding more and more data to a personal profile drawn from their history of online interactions (Karaj, Person, et al. 2019).

While tracking data is typically anonymized, research has shown it possible to reveal users’ real identities by linking information from many data points. Distinctive patterns in a given user’s browsing history can be correlated with social media profiles, thus revealing personal data about their personality, sentiments, and social relations. In a more direct manner, authenticated users of platforms such as Google and Facebook are tracked by their personal user accounts (Su, Goel et al. 2017). As a result, online user tracking is nearly ubiquitous, and the user profiles compiled by tracking data are commodified and exploited for commercial purposes by websites, advertising networks, and data warehouses.

The web itself is barely 30 years old, and was originally intended to help scientists manage and share information around the world (CERN n.d.). The turn toward an advertising-based model of the web is more recent. Many people, including me, argue that the commercial turn was not inevitable, and there can be other ways to design a global information system for human betterment and the common good. To explain how we got from an open and noncommercial web to a commercial network dominated by a handful of technology giants, I first explore the history of user tracking and its role in the origins of the commercial Internet.

A Short History of Online Tracking

It started with a cookie. Specifically, the Persistent Client State HTTP Cookie, a string of text inserted in a web page to send information from a browser to a web server. The first cookie implementation was developed in 1994 by Lou Montulli and John Giannandrea while working on browser technology at Netscape Communications (Kesan & Shah 2004).

Prior to tracking methods like cookies, connections between a browser client and a web server were “stateless,” meaning that no information about a browser connection (session) is saved by the server. The client requests a web page, but the server has no way to relate the client with past or future requests, and the client has no way to store information about user interactions during the session (Murray 2019, Reschke & Fielding 2014). The browser cookie was developed to allow servers to store data in the client and retrieve it at a later time (Netscape Communications 2001).

Montulli and Giannandrea were working to enable storage of data about items selected in an online shopping cart. This requires a “stateful” connection between client and browser that retains information about user interactions. Their first iteration of a cookie allowed the web server to determine if the client was connecting for the first time, or was a repeat visitor. This kind of cookie use can be beneficial for the user e.g. by retaining information they filled out in form fields, and keeping alive authenticated server connections. It can also be beneficial for the server operator to track browsing activities such as page views and referral paths to and from their website. This information can help them improve the design and performance of their site.

The potential for invasive user surveillance was not appreciated in the beginning, but in retrospect the privacy issues have become obvious. The earliest public concerns I found concerning the impact of cookies on privacy were raised on April 1, 1996, when the Financial Times published a column cautioning users of the web that they are being watched by the sites they visit.

“Technology is already in place – and ready to be put to use on the World Wide Web of the Internet – that will allow Web site owners to gather an alarming range of information on the people who look at their Web pages from PCs at home…the tale of these cookies is an illustration of the possibilities that Internet Marketing opens up” (Jackson 1996).

By the time this Financial Times column was published those possibilities were already opening, and the web was being transformed. ”Before cookies, the Web was essentially private,” commented Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig to The New York Times in 2001. ”After cookies, the Web becomes a space capable of extraordinary monitoring’’ (Schwartz 2001).

Birth of the Commercial Internet

In the mid 1990s, two innovations were on track for convergence in ways that would profoundly change the internet, from an open system for scientific collaboration and public communication, to a platform dominated by large technology and marketing corporations. Legacy businesses, entrepreneurs, and dot-com startups were searching for a business model for the web, while early-web exuberance attracted massive investments by “angel” investors and venture capital funds. As it had been with American radio and television broadcasting, advertising began to seem like the best bet (Wolf 1998).

DoubleClick, one of the earliest successful Internet advertising companies, was formed in a basement in 1995. The company developed a system for distributing banner ads to a network of websites, and began enrolling both advertisers and sites to display them. The DoubleClick ad network used cookies to measure ad impressions and to target visitors (Colao 2013). In 1999 DoubleClick purchased its leading competitor NetGravity, along with its ad server technology. “While DoubleClick is known in the industry for its sales force, NetGravity is known for its technology,” reported The New York Times. “The combined companies’ ability to offer a variety of services will become increasingly important as Internet advertising grows” (Napoli 1999).

By 2000 the DoubleClick ad network was inserting trackers and ads on some 1,500 websites, and had merged with the consumer data co-op Abacus, a company with a growing database of offline buying habits in the U.S. (AdExchanger 2018). Speculation that DoubleClick was combining online and offline data about consumers led to growing public concerns about personal data privacy. The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) filed a complaint against DoubleClick, accusing the company of privacy violationsand deceptive business practices. At issue were DoubleClick’s claims that consumer data collected by its cookies would remain anonymous. Investigations were launched by the Federal Trade Commission and the New York Attorney General (Clausing 2000).

Less than a year later a federal judge ruled that “DoubleClick never used or disclosed consumers’ personally identifiable information for purposes other than those disclosed in its privacy policy” (U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York 2001). The ruling established a precedent that a company’s privacy policy gives adequate notice to consumers, regardless of their understanding of how tracking collects their data.

“DoubleClick rapidly became the dot-com era’s leading provider of targeted advertising, compiling a database of hundreds of millions of consumer profiles,” wrote Matthew Craine, a media and culture scholar at Miami University. “An industry of surveillance advertisers followed suit, led most forcefully by Google and Facebook, whose leaders pushed the boundaries of data collection and sought to redefine privacy norms” (Craine 2020).

Meanwhile another company was launching the second leg of AdTech: online analytics. In 1995 Quantified Systems, Inc. was a web development and hosting company in San Diego, California. One of the company’s founders, Paul Muret, developed a rudimentary server log analyzer to measure bandwidth use by its customers and facilitate billing. By 1997 the software could track page views and referring urls (Crosby 2017). But tracking at scale was of no use unless the data it returns could be analyzed. “One of our large clients was struggling with the fact that it took 24 hours to process a single day’s worth of website tracking results,” explained Muret in an interview. “We tried out our new analytics tool, and it took 15 minutes to process the same data.” The analytics tool was given the name Urchin, and as the analytics side of its business became profitable, Quantified Systems was renamed the Urchin Software Corporation (Roque 2013).

As other companies were moving into the web analytics business, Urchin kept its lead as an innovator by developing a site license model that proved very popular with customers. By 2003 the company had contracts with large corporate and government clients including Honda, Earthlink, Rackspace, and the U.S. Department of Defense. Urchin was not only highly profitable; it became a standard analytics platform for thousands of websites (Roque 2013).

Early versions of Urchin depended on data from server logs. Urchin version 4 augmented log files with javascript cookies. Urchin co-founder Scott Crosby explained in a 2016 blog post:

“Most of our competitors at the time used either logs only (old school) or javascript/cookies only (WebSideStory, etc.), and both necessarily missed out on a lot of available information. Urchin was the first to use both data sources in one unified collection method, neatly contained in augmented access-log files” (Crosby 2016).

By version 6 [Figure 1], Urchin had what Crosby called a “killer feature” that was a little too advanced in terms of privacy: a so-called Campaign Tracking Module that could drill down into the browsing history of individual users. “If this sounds potentially, um, sensitive,” said Crosby, “that’s because it is” (Crosby 2016).

Figure 1: The Urchin 6 dashboard with its “killer app,” access to the browsing history of users. Source: Crosby 2016.

Google Enters the Ad Business

Google was incorporated in 1998, offering a new kind of search engine with a mission “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” (Google, Inc. n.d.). Since then the company has become the global leader in online advertising, but Google didn’t begin selling ads until 2000. Google’s first ad platform allowed advertisers to purchase keywords, phrases, and categories. When these terms were used in a Google search, an advertisement from the company that purchased them was displayed at the top of the search results page highlighted as “sponsored links” (Google, Inc. August 2000). Advertising opportunities were initially limited to some 350 “premium sponsors.” The service worked so well that in October Google expanded availability to any advertiser, calling the new service AdWords (renamed in 2018 as Google Ads). Clients had real time access to statistics on ad impressions and click-through rates (Google, Inc. October 2000). But at launch AdWords didn’t use cookies, and didn’t provide the range and depth of data available through online analytics today.

Over the next few years Google was growing rapidly, and had resources to expand its advertising technologies and products. It began by acquiring smaller companies with better technology. The first significant acquisition in the marketing realm was the purchase of Applied Semantics and its patents in April 2003. Applied Semantics had a targeted advertising method it named AdSense, and a network to display ads on thousands of websites. Applied Semantics’ targeting was based on “semantic text processing,” which according to Google’s characterization of the deal “understands, organizes, and extracts knowledge from websites and information repositories in a way that mimics human thought and enables more effective information retrieval” (Google, Inc. April 2003).

With the acquisition Applied Semantics, AdSense was renamed Google AdSense and it remains one of Google’s core products. “AdSense was a game-changer for the ad tech industry because it made it easy for advertisers to target consumers across the millions of fragmented websites online,” reported Ben Kneen, a writer for Ad Ops Insider, “and it gave publishers of any size a quick and easy way to make money from their content (Kneen 2015).

But AdSense didn’t support what we think of today as tracking or analytics. It functioned by parsing the text content on web pages to analyze keywords and phrases, and displaying ads that in theory matched the content. And it made no use of cookies or other forms of user tracking.

Origins of Google Analytics

In the summer of 2004 Google, Inc. held an IPO, raising 1.9 billion dollars (Investopedia 2015). Firmly in the advertising business and with plenty of capital, Google went shopping for an analytics solution. Company representatives approached Urchin at the 2004 Search Engine Strategies conference in San Jose. An offer to acquire the company was made, and the acquisition was consummated in April 2005. “We want to provide web site owners and marketers with the information they need to optimize their users’ experience and generate a higher return-on-investment from their advertising spending,” said Jonathan Rosenberg, Google’s vice president of product management. “This technology will be a valuable addition to Google’s suite of advertising and publishing products” (Google Inc. 2005). Urchin’s management team was hired by Google, and Paul Muret became Google’s VP and Director of Engineering. He remains at Google as VP of Product, Google AI and Health (Muret n.d.).

Google Analytics was announced on November 14, 2005, and immediately offered to websites for free. AdWords users could access Google Analytics reports from their AdWords dashboard. The new analytics platform could also work with non-Google ad networks. “Google Analytics is also able to track the results of any online marketing campaign, including banner ads, referral links, email newsletters, and organic and paid search” Google announced (Google Inc. November 2005).

But one part of Urchin was left behind: the Campaign Tracking Module that captured the browsing interactions and history of each individual visitor. Muret explained that “Google wouldn’t touch this feature and it was summarily axed, never to return” (Crosby 2017).

Google Assembles the Pieces

By 2007 Google Analytics was in use by hundreds of thousands of websites, and its data capacities and user interface were becoming increasingly mature (Google Analytics Solutions 2007). Google Search held the status of top search engine, and Google’s share of the paid search market had reached 75 percent. DoubleClick’s success had showed that the market for display advertising on the web was heating up. But Google AdWords was designed to display simple text ads on search results pages, not to distribute and display visual ads on other websites. Google had launched an embryonic display ad network catering to small websites and personal blogs. But Google executives sensed a growing opportunity and decided to make a bid for DoubleClick. The acquisition was completed on March 11, 2008. Data scientist Tony Yiu said of the deal:

“The DoubleClick acquisition was a massive coup for Google. In 2007, DoubleClick was a company with expertise in serving display ads and that owned tons of relationships to both key websites and advertisers (who were all users of its software). And perhaps even more attractive to Google, they were right about to establish the DoubleClick Ad Exchange, a marketplace where advertisers could bid for ad inventory (spots on websites where an ad could be displayed) in realtime” (Yiu 2020).

The acquisition of DoubleClick positioned Google to broker transactions between buyers of online ads and sellers of online ad space, charging a small fee for every transaction. It also gave Google access to leading advertisers and the largest digital ad network in the world. The acquisition of Urchin gave Google the most advanced analytics platform, and more tracking data about website users than anyone else.

![]()

Figure 2: In 2020 Google tracks nearly 80 percent of all web traffic. Source: whotracks.me.

These two acquisitions were the key pieces in Google’s transition from a company hosting an innovative search engine, to a marketing company with a dominant online advertising platform. Today Google is the market leader in digital advertising, and Google trackers are present on 79 percent of websites worldwide (WhoTracksMe n.d.) (Figure 2).

The World of Google Analytics

In any explanation for the rise of tracking and online advertising, we could be forgiven for overlooking the role of analytics. We might think of the subject as subordinate to tracking, if we think of it at all. But tracking data is meaningless without analysis, and targeted online advertising can’t function without the meanings derived from analytics.

Google Analytics creates meaningful information by analyzing tracking data to make it actionable in targeted advertising. GA provides ad performance data to the advertiser to inform better targeting, messaging, and ROI. Analytics are now essential for competitive online advertising, and Google Analytics is the king of online analytics.

It is important to note that Google leverages the entire constellation of its other platforms to collect data and compile profiles containing personal information. When a user authenticates into any Google product, their use of the product is mined for data by Google: Google Search, Google Chrome, Google Calendar, Google Drive, Google Home, Google Maps, YouTube, Google Assistant, Google News, Blogger, Gmail, Google Calendar, Google Drive, Google Translate, Google Surveys, Android, Google Pixel, Google Nest, Google Home, and more. To be clear, Google uses that data for its own purposes such as product improvement, and does not share it with or sell it to third parties. But every byte of data adds to the picture of everything Google knows about each individual user (Nield 2019).

It’s also fair to note that many other companies track online users, and some have their own analytics systems and advertising networks. Facebook is second to Google in leveraging personal data for commercial purposes. We also know from the Cambridge Analytica scandal that analytics derived from Facebook user data was used to influence voters in the 2016 U.S. election (Halpern 2018). But Google was the early innovator and remains the runaway leader of online tracking, analytics, and advertising. Given the weight of Google’s dominance, the many privacy issues raised by its products and practices warrant critical examination.

Many other commercials systems warrant more research concerning their impact on personal privacy and consequences for society. But the focus of this report is Google Analytics, so as to begin drawing a more complete picture of its role in the emergence and impact of the AdTech industry. To that end I present an under-the-hood look at GA’s methods for collecting user data, and the scope of the data itself.

Google Analytics Tracking Methods

Google has made its tracking technology as easy as possible to use throughout its marketing platforms. The tracking itself begins with a free account in Google Analytics and a few lines of JavaScript. The GA script has evolved since Urchin but the methods are essentially the same. The most recent version, used in Google Analytics 4, is the gtag.js script. Google refers to this script as a “tag,” and tag nomenclature is used throughout Google’s documentation. The term “tag” might seem more innocuous than “tracker,” but the two terms are now synonymous (Google Tag Manager Help n.d.). In digital advertising, first- and third-party trackers are referred to as first- and third-party tags.

The GA tag is inserted in the head section of a webpage:

Most websites today use a content management system such as WordPress, SitePoint, BrightSpot, etc., which automate insertion of a tag across the entire site. When someone visits a webpage, the tag will set a cookie in the browser and load additional JavaScript to send data to the server. The script generates a unique Client ID that “pseudonymously identifies a particular user, device, or browser instance” (Google Developers n.d.) The Client ID is stored in a first-party cookie that will persist for two years before expiring unless deleted by the user. This allows GA to recognize the client in later visits. The data is accessible through the GA dashboard, with a 24 hour lag time (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Google Analytics dashboard today. Source: Google Analytics.

Google provides extensive information on the type and scope of data collected, grouped by categories of data fields. The following is derived from Google Analytics documentation.

Traffic Source field data includes the referral source that brought the user to the website, and information for ad targeting including the Google Ads ID which allows the visit to the visit to be associated with the site owner’s advertising campaigns.

System Information fields contain data captured from the visitor’s device, such as operating system, browser version, screen resolution, color depth, viewport size, Flash version, and much more. If a website user is blocking cookies, this data can be useful for “fingerprinting” the unique characteristics of the user’s system, another form of tracking.

Other fields are associated with a particular website visitor, such as Client ID and User ID. The User ID is a “a known identifier for a user provided by the site owner/library user,” and facilitates tracking of the user across the web and all devices they use. The User ID is composed of a GA-generated string of characters or numbers. For users logged in to another Google product such as Gmail or Chrome, Google adds user tacking data to their account profile.

Each field is formatted as a key value pair, for example “uid=as8eknlll”, where uid is the key and as8eknlll is the value. The GA operator can easily create their own custom fields for visitor interactions they define. For example, they can assign a class or an id attribute for a specific webpage element, such as a link. When the link is clicked, GA records it as an “event.”

Data from all events is sent back to Google as a “payload” comprised of a collection URL with any number of key value pairs as parameters (Figure 4). (Earlier versions of GA attach the payload to a GIF image on a Google analytics server.)

Figure 4: The data payload sent from a web page to Google Analytics with a number of key value pairs. Source: Google documentation.

The data is encrypted and Google claims to never share it with third parties. But another Google product, the Google Tag Manager, makes that claim irrelevant.

Google Tag Manager and Third-Party Trackers

Adding third-party and custom tags to a web page was once a job for web developers, as each tag had to be added to the GA tracking code. Google Tag Manager was designed to enable non-technical professionals to add tags through a dashboard interface. Importantly, Google Tag Manager is not limited to Google Analytics tags; it can easily be used to include any number of third-party tags. As a result the Google tag facilitates tracking by potentially hundreds of third parties with different technologies, privacy policies, and data security practices. Google may keep its promise to never sell user data, but third-party tags open the door to others who don’t make that commitment (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The Google Tag Manager dashboard, which can be used to define custom tags for sending specific browser interactions to Google Analytics.

Importing and Exporting Data from Google Analytics

Google Analytics can process thousands of website user interactions collected through tracking. But tracking data isn’t the only possible input to GA. The enterprise version of Google Analytics, Google Analytics 360, allows the GA user to import data from other online and offline sources, for example CRM systems or product catalogs. GA 360 also has an API for exporting raw data into other systems and applications. This opens the door to merging anonymized data with personally identifiable information, potentially leading to a host of damaging privacy violations. Data systems can be hacked, resulting in leakage of personal information, identity theft, and other harms. Once the data leaves the GA platform, privacy and security are in the hands of the GA account owner, who may have different standards for privacy, security, transparency, and accountability.

A World Wide Web Full of Trackers

“What if you could see what you’ve been missing about your customers? You may have first-party data on your users, which can tell you what pages they visit on your site and other information they’ve given you directly. However, even with the vastest collection of first-party data, you only get a narrow view of your customers behaviors and interests. What do your customers do outside your sites and apps? What content do they consume? What interests do they have? What do they eat, where do they shop, how do they work their worlds, etc.?” (Lotame 2020)

Digital ad networks and data brokers now promote tracking as a competitive advantage, resulting in a flood of trackers throughout today’s web. The “adsbydomain” website at https://adsbydomain.fouanalytics.com/ scans websites for trackers and ad servers. People Magazine (people.com) showed 435 trackers. A scan of aol.com showed 565 trackers (Figure 6). The New York Times site (nytimes.com) loaded a mere 97 trackers (Fou 2020 December 2020) which is still more than ten times the average for all websites.

![]()

Figure 6: A map of aol.com‘s first- and third-party trackers and ad server requests, December 2020. Source: https://adsbydomain.fouanalytics.com/q/aol.com.

This is possible because first-party trackers can load third-party trackers which can load more third-party trackers. And many websites have more than one first-party tracker.

The number of trackers on a given website is a meaningful general metric of tracker presence. Another interesting metric is the site reach of specific trackers, i.e. the number of websites where a given tracker is present. Augustine Fou, an early digital marketer who now audits bot-driven ad fraud (another problem), analyzed both tracker site presence and site reach on the top 10,000 sites, and plotted the relationship of both metrics for a deeper picture of tracker prevalence (Fou 2019). Unsurprisingly, Google trackers have far greater site presence and site reach than any other tracker source (Figure 7).

![]()

Figure 7: Graph plotting website tracker presence and site reach for the top 10,000 sites where a given tracker was present on at least one page, 2019. Source: whotracksme.

Google Steps to Protect Privacy

While Google is the runaway leader in tracking and digital advertising, it is now making notable efforts to lead in protecting user privacy. For example, in January 2020 Google announced that it will drop support for third-party cookies in its Chrome web browser within the next two years (Chromium Blog 2020). Google’s Privacy Policy is comprehensive and written in clear language (Google, Inc. 2020). Google account privacy settings allow users to opt out of important parts of Google tracking, and to view and delete personal information. Importantly, Google expresses a commitment to complying with data privacy and protection laws, and appears to be compliant with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulations (Malcolm 2017). The company also offers tools to help other websites comply with the GDPR (Google Support n.d.).

But many people use browsers other than Chrome, so large-scale browser tracking will continue. Google Tag Manager continues to help websites load third-party trackers. Google cannot control what happens after third-party tracking collects user data. Even if cookies were eliminated from the web, tracking remains possible by using a fingerprint of the user’s device and browser settings. More importantly, pervasiveness of AdTech has fueled the rise and rapid growth of the digital advertising industry, and transformed the Internet from a public space to a domain of commercial transactions. It seems unlikely that new privacy regulations and tracker-blocking technology will transform it back.

A Three-Part Conceptual Model of Adtech

I have argued that a crucial element has been neglected in research and critical examinations of online tracking and advertising. This article attempts to rectify that neglect by highlighting the role of online analytics in general, and Google Analytics in particular, in the rise of AdTech and commercialization of the Internet. Personal data is important for targeted advertising, but more important is actionable personal data. As an aide to make visible what has been hidden, I propose a three-part model of AdTech consisting of tracking, analytics, and advertising (Figure 8).

Figure 8: A three-part conceptual model of AdTech.

The three parts of this model define the foundation of the commercial Internet. They are interactive and interdependent: Tracking feeds raw user data into an analytics platform; the analytics platform processes the raw data into actionable information for targeted advertising; advertising leads to user interactions that generate more tracking, and the cycle begins again. Assuming each part of the model performs its function well, the AdTech system becomes more powerful with each iteration of the cycle.

Since the role of analytics has been largely invisible in discussions about tracking and advertising, this model makes it visible for closer examination. It may be useful as a lens for future research on other facets of the Internet including technology, economics, business practices, politics, policy and regulation, and not least privacy and security. And despite the breadth of research relating to Internet studies, there is much more Internet history that has yet to be explored.

Conclusion

Google didn’t invent online tracking, analytics, or advertising. It did something much more consequential by combining them on an industrial scale. Browser cookies were common before Google. But Google Analytics supercharged cookies by making it easy to add them to any website. In so doing, Google Analytics initiated tracking on a global scale, flooded the field of advertising with personal data, and facilitated the targeting of online users with advertising tailored to their demographics, location, behavior, and interests. In this environment, personal data has become increasingly valuable as a commodity, and is aggregated and monetized by websites, advertisers, and data brokers. Anonymized online data from analytics can be de-anonymized in combination with offline data, potentially resulting in exposure of personally identifiable information. The scope of this data has created difficult new challenges for the protection of personal privacy and security. The proposed three-part conceptual model of AdTech makes visible the role of analytics transforming raw personal data into actionable information. It is offered here as a potential lens to examine and fill a conspicuous gap in existing research.

There is much more to this story. The rise of AdTech transformed the Internet from a public commons to a domain of commerce and competition for market share, and has led to normalization of online surveillance and commodification of personal data which our privacy conceptions and regulations are only beginning to address. Google wrote the first chapters, but it is unclear if anyone can write the ending.

References

AdExchanger. (2018, October 29). ‘It Wasn’t A Job, It Was A Cult!’: The Definitive Oral History Of DoubleClick. AdExchanger. https://www.adexchanger.com/ad-exchange-news/it-wasnt-a-job-it-was-a-cult-the-definitive-oral-history-of-doubleclick/

Black, A., & Mak, B. (2020). Period, Theme, Event: Locating Information History in History. In Information and Power in History: Towards a Global Approach. Routledge. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:25457/

CERN. (n.d.). A short history of the Web. Retrieved December 6, 2020, from https://home.cern/science/computing/birth-web/short-history-web

Chromium Blog. (2020, January 14). Building a more private web: A path towards making third party cookies obsolete. Chromium Blog. https://blog.chromium.org/2020/01/building-more-private-web-path-towards.html

Clausing, J. (2000, February 17). U.S. Investigating DoubleClick Over Privacy Concerns. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/02/17/technology/us-investigating-doubleclick-over-privacy-concerns.html

Colao, J. J. (2013, August 12). Gilt, MongoDB, DoubleClick: Meet The Duo Behind New York’s Biggest Tech Companies. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jjcolao/2013/07/24/gilt-10gen-doubleclick-meet-the-duo-behind-new-yorks-most-successful-tech-companies/

Crain, M. (2020, December 8). How Surveillance Advertising Seized Our Data and Hijacked the Web. The Reboot. https://thereboot.com/how-surveillance-advertising-seized-our-data-and-hijacked-the-web/

Crosby, S. (2016, September 2). Urchin Software Corp. – The unlikely origin story of Google Analytics, 1996–2005-ish. Medium. https://urchin.biz/urchin-software-corp-89a1f5292999

Fou, A. (2019, February 22). Updating our tracking prevalence metrics. https://whotracks.me/blog/updating_our_tracking_prevalence_metrics.html

Fou, A. (2020, June 3). Those Ad Fraud Bots Did What? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/augustinefou/2020/06/03/those-bots-did-what/

Fou, A. (2020, July 25). How Many Ads And Trackers Does ONE Page Load? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/augustinefou/2020/07/25/how-many-ads-and-trackers-does-one-page-load/

Fou, A. (2020, December 9). FouAnalytics—Ads By Domain. https://adsbydomain.fouanalytics.com/q/people.com

Google Analytics. (n.d.). Tracking Code Overview | Google Analytics. Google Developers. Retrieved December 9, 2020, from https://developers.google.com/analytics/resources/concepts/gaConceptsTrackingOverview

Google Analytics Solutions. (2007, May 8). New Version of Google Analytics! Google Analytics Solutions. https://analytics.googleblog.com/2007/05/new-version-of-google-analytics.html

Google Developers. (n.d.). Add additional products | Global site tag (gtag.js). Google Developers. Retrieved December 9, 2020, from https://developers.google.com/gtagjs/devguide/add

Google Developers. (n.d.). Measurement Protocol Parameter Reference. Google Developers. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from https://developers.google.com/analytics/devguides/collection/protocol/v1/parameters

Google, Inc. (n.d.). How we started and where we are today—Google. Retrieved December 8, 2020, from //www.google.com/our-story/

Google, Inc. (2000, August 16). Google’s Targeted Keyword Ad Program Shows Strong Momentum with Advertisers – News announcements – News from Google – Google. http://googlepress.blogspot.com/2000/08/googles-targeted-keyword-ad-program.html

Google, Inc. (2000, October 23). Google Launches Self-Service Advertising Program – News announcements – News from Google – Google. http://googlepress.blogspot.com/2000/10/google-launches-self-service.html

Google, Inc. (2003, April 23). Google Acquires Applied Semantics – News announcements – News from Google – Google. http://googlepress.blogspot.com/2004/04/google-acquires-applied-semantics.html

Google, Inc. (2005, March 28). Google Agrees To Acquire Urchin – News announcements – News from Google – Google. http://googlepress.blogspot.com/2005/03/google-agrees-to-acquire-urchin_28.html

Google, Inc. (2005, November 14). Web Analytics Free of Charge, Courtesy of Google – News announcements – News from Google – Google. http://googlepress.blogspot.com/2005/11/web-analytics-free-of-charge-courtesy_14.html

Google, Inc. (2020, September 30). Privacy Policy – Privacy & Terms – Google. https://policies.google.com/privacy?hl=en-US

Google Support. (n.d.). Tools to help publishers comply with the GDPR – Google Ad Manager Help. Retrieved December 9, 2020, from https://support.google.com/admanager/answer/7666366?hl=en

Google Tag Manager Help. (n.d.). About Tags—Tag Manager Help. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from https://support.google.com/tagmanager/answer/3281060

Halpern, S. (2018, March 21). Cambridge Analytica, Facebook, and the Revelations of Open Secrets. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/cambridge-analytica-facebook-and-the-revelations-of-open-secrets

Investopedia. (2015). If You Had Invested Right After Google’s IPO. Investopedia. Retrieved December 8, 2020, from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/active-trading/081315/if-you-would-have-invested-right-after-googles-ipo.asp

Jackson, T. (1996, April 1). This bug in your PC is a smart cookie. Financial Times. https://archive.org/stream/FinancialTimes1996UKEnglish/Feb%2012%201996%2C%20Financial%20Times%2C%20%2312%2C%20UK%20(en)#page/n29/mode/2up

Karaj, A., Macbeth, S., Berson, R., & Pujol, J. M. (2019). WhoTracks .Me: Shedding light on the opaque world of online tracking. ArXiv:1804.08959 [Cs]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1804.08959

Kesan, J. P., & Shah, R. C. (2004). Deconstructing Code (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 597543). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=597543

Kneen, B. (2015, July 19). A History of Ad Tech Acquisitions. Ad Ops Insider. https://www.adopsinsider.com/ad-ops-strategy/a-history-of-ad-tech-acquisitions/

Lotame. (2020, July 8). Understanding the Panoramic View of Your Consumer. Lotame. https://www.lotame.com/understanding-the-panoramic-view-of-your-consumer/

Malcolm, W. (2017, August 8). Getting ready for Europe’s new data protection rules. Google. https://blog.google/around-the-globe/google-europe/gdpr-europe-data-protection-rules/

Muret, P. (n.d.). Paul Muret | LinkedIn. Retrieved December 7, 2020, from https://www.linkedin.com/in/paulmuret/

Murray, V. (2019, February 7). Statefulness in a Stateless Web. Medium. https://medium.com/@t0ri/being-stateful-in-a-stateless-web-8185ed777048

Napoli, L. (1999, July 14). DoubleClick Buys NetGravity. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/tech/99/07/cyber/articles/14advertising.html

Nield, D. (2019, May 27). All the Ways Google Tracks You—And How to Stop It. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/google-tracks-you-privacy/

Netscape Communications. (2001, April 13). Persistent Client Side State—HTTP Cookies. https://web.archive.org/web/20010413112429/http://home.netscape.com/newsref/std/cookie_spec.html

Reschke, J. F., & Fielding, R. T. (2014, June). Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP/1.1): Message Syntax and Routing. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7230

Roque, C. (2013, April 5). The Real Story on How Google Analytics Got Started, by @attendly. /the-real-story-on-how-google-analytics-got-started/

Schwartz, J. (2001, September 4). Giving the Web a Memory Cost Its Users Privacy. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/04/business/giving-web-a-memory-cost-its-users-privacy.html

Su, J., Shukla, A., Goel, S., & Narayanan, A. (2017). De-anonymizing Web Browsing Data with Social Networks. Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, 1261–1269. https://doi.org/10.1145/3038912.3052714

U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. (2001). In Re DoubleClick Inc. Privacy Litigation, 154 F. Supp. 2d 497 (S.D.N.Y. 2001). Justia Law. Retrieved December 7, 2020, from https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/154/497/2429654/

W3Techs. (2020, December). Usage Statistics and Market Share of Traffic Analysis Tools for Websites. https://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/traffic_analysis

Weller, Toni. 2007. “Information History: Its Importance, Relevance and Future.” Aslib Proceedings 59 (4/5): 437–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530710817627.

WhoTracksMe. (n.d.). WhoTracks.me | Trackers. Retrieved December 6, 2020, from https://whotracks.me/trackers.html

Wolf, M. (1998). Burn Rate: How I Survived the Gold Rush Years on the Internet. Simon & Schuster.

Yiu, T. (2020, May 6). Why Did Google Buy DoubleClick? Towards Data Science. https://towardsdatascience.com/why-did-google-buy-doubleclick-22e706e1fb07